Daily Post Editorial

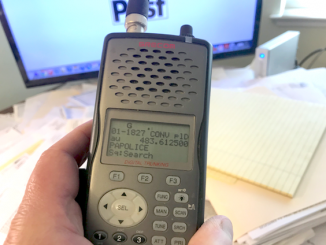

Palo Alto police have decided to encrypt their radio transmissions, a move that will severely limit the ability of journalists to do their jobs. Moreover, members of the public who are interested in keeping abreast of crime in their neighborhood will no longer be allowed to listen into these transmissions, even though their tax dollars fund the police radio system.

Instead of receiving factual information from these radio broadcasts, rumors will flourish, especially in emergency situations.

Encrypting police radio transmissions ends a tradition that goes back to the 1940s, when the public began listening to radio traffic between dispatchers and officers out in the field. At the time, police may not have liked the idea that the public could monitor their activities, but the Federal Communications Commission made it clear that the airwaves belong to the public, and the public has a right to hear what goes over them.

Today, however, many police departments are reducing their transparency in the wake of criticism spurred by the death of George Floyd.

Reduced media access

A few months ago, Palo Alto police decided reporters could no longer talk one-on-one with police to obtain information about police activities. Instead, questions from reporters have to be submitted through the city’s website. Sometimes the police would answer the questions on the same day, but often reporters wouldn’t hear back for a couple of days. And this awkward system made it much harder for reporters to ask follow-up questions, which are intended to ensure the accuracy of information reporters receive.

And there are other signs the department has been reducing transparency. For five years, city and police officials kept secret an investigation into police Capt. Zach Perron’s use of the n-word in front of a black officer, who later resigned. City Council members weren’t told about the investigation even though the city could have faced millions of dollars in civil liability had the black officer decided to sue. Instead, he took a job with another law enforcement agency.

False police report alleged

Then there’s the case of Gustavo Alvarez, who was violently beaten while in handcuffs by then-Sgt. Wayne Benitez in 2018. Benitez didn’t realize it at the time, but his attack on Alvarez was caught on a surveillance camera. He filed a police report that didn’t mention the attack, according to Alvarez’s attorneys, who obtained a $572,500 out-of-court settlement from the city.

The video shows three other officers watched the attack, but they all kept silent — another sign of the lack of transparency in the Police Department.

If Palo Alto Police had a good relationship of trust with the community and the news media, Chief Robert Jonsen’s decision to encrypt the radio transmissions might be acceptable. But this department has done little in the past few years to show it can be trusted, and City Council is naive to believe that less transparency will result in improvements.

No public process

Jonsen’s decision to encrypt radio transmissions was made without the public process that’s common at City Hall. This decision was made behind closed doors with no public input, no attempt to reach out to stakeholders and no advice from the elected policy-makers, the City Council.

Jonsen said police were encrypting the signals to bring the city into compliance with a requirement by the California Department of Justice. The agency set a Dec. 31 deadline for police departments to come up with a plan to keep personal information like names, driver’s license numbers and Social Security numbers from being heard by the public.

The Department of Justice gave the state’s local police departments two paths to take:

1. encrypting all radio transmissions, or

2. restricting dispatchers and officers from broadcasting protected information while allowing other transmissions to continue.

The second alternative could be accomplished by an officer pulling out a cellphone and calling the dispatchers in the basement of City Hall.

Jonsen said this alternative isn’t practical, but it’s been the practice of his officers for years. People who have listened to the police radio in Palo Alto for any amount of time will hear the phrase “call radio,” which means the officer should call the dispatchers to discuss something confidential that shouldn’t go out over the air.

Jonsen said that no other department in the area has chosen this less restrictive approach. But that doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be considered here. Palo Alto hasn’t been afraid to choose its own way in the past. We’ve done this by carefully considering the pros and cons and allowing the public to weigh in.

Who decides policy?

Police policy in Palo Alto is typically decided by the police chief with no input from City Council. Yet it is council’s job to set city policy, not the police.

It seems to us that council members haven’t wanted to become engaged in police policy, perhaps because they don’t understand how the department operates.

It’s time for council to start taking an active role in setting overall policy for the police, and a public hearing examining encryption would be a good start.

Council should put this matter on its agenda so that Jonsen can be questioned publicly, and he can defend his decision. If he made the right decision, it should be able to withstand public scrutiny.

It would be helpful to know if police have any examples of the harm un-encrypted broadcasting has done. Instead of dealing with theories and hypotheticals, it would be useful to know what this policy is trying to prevent.

The police demand that Apple turn over the encryption keys when they want to search somebody’s iPhone. But when the roles are reversed and the public wants to listen to the police radio, the police insist their conversations should be encrypted.

Makes you wonder who is in charge? The city council, whom we elect, or the police, a paramilitary organization?

If PAPDs track record were better on transparency it would matter not a whit. Nor would it matter what other police departments are doing. As long as there is a less onerous, more transparent alternative, Council should require that option for the PAPD.

The press protects the public, and the public should have all the access it has a right to under this law to protect our community. It is not up to the police to unilaterally decide the extent of our First Amendment rights will be taken from us.

Come on council members – start exerting oversight of the police, including the Chief.