BY ALLISON LEVITSKY

Daily Post Staff Writer

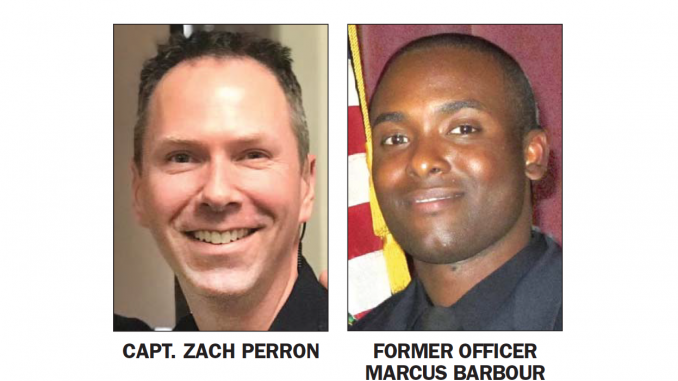

Palo Alto police Capt. Zach Perron was investigated for using a racial slur while speaking to a black officer — and the probe wasn’t shown to the city’s independent police auditor, keeping it out of the public eye.

Perron declined to comment on the allegations against him or on the internal investigation, and the chief at the time, Dennis Burns, didn’t return a request for comment.

It’s unclear what the outcome of the investigation was, or whether Perron was disciplined.

Former Palo Alto police Officer Marcus Barbour, who now works for a different law enforcement agency, told the Post that Perron made a joke using the word “n****s” to him after Barbour rescued a black felon who had jumped into San Francisquito Creek while Barbour was chasing him.

Barbour, a U.S. Army veteran, was sworn in to the department in July 2013. He saved the felon’s life by jumping into the creek after a foot chase on Jan. 28, 2014, six months after joining the force. Barbour went on to be awarded the department’s Medal of Valor for the rescue.

After Barbour returned to the police station the day of the rescue, Perron allegedly joked to him that “n***as don’t swim.”

Perron made the comment in a hallway in front of other officers, Barbour said.

Barbour leaves, Perron promoted

Barbour left the department in January 2017, around the time Perron was promoted to captain and shortly after Chief Burns retired. Barbour declined to comment further about the incident, citing concerns about retaliation and the wishes of his current union president.

Perron, a Palo Alto native, joined the department in 1998, the year after he graduated from Stanford.

As the coordinator of the Investigative Services Division, Perron oversees the department’s detectives and traffic enforcement.

Until last year, Perron also ran public affairs, talking to reporters, writing press releases and appearing on camera for TV interviews.

Reaction to comment

In early 2017, an officer who heard Perron make the comment in 2014 told Palo Alto police Agent Marianna Villaescusa about it. Villaescusa said she was “stunned and actually in disbelief” to hear that Perron had used the N-word at work.

Villaescusa declined to identify the officer who told her about Perron’s comment.

She said she hadn’t previously heard Perron say anything overtly racist in their years of working together, noting that her husband, Sgt. Ken Kratt, was the best man in Perron’s wedding.

“How does somebody in that type of position think that that’s OK?” Villaescusa asked. “I have a hard time accepting that (Perron) is naive or ignorant to the history and hate associated with the N-word.”

Complaint taken to city manager

Villaescusa took her concern about Perron’s comment to then-City Manager Jim Keene and the Rev. Paul Bains, who serves as the department’s chaplain. Keene didn’t return the Post’s requests for comment.

“Keene said he had heard something was said, so I asked him if he wanted to hear the actual words that were used,” Villaescusa said. “He looked pretty uncomfortable, and he asked the deputy (city) manager what she thought. I decided they needed to hear it, so I told them using the entire N-word. I also pointed out how uncomfortable the officer who had to hear it must have felt.”

Bains said he doesn’t know whether he was the official complainant who prompted the internal investigation.

He declined to say more, citing concerns about privacy.

“The officers trust me, and I can’t break their confidentiality. I don’t know where the official complaint came from, so I can’t elaborate on that, and it wouldn’t be good for me to do it anyway,” Bains said. “Those officers would not talk to me anymore.”

Bains noted that he didn’t follow up with the city on the outcome of the investigation because the alleged conduct didn’t seem to be part of a recurring problem.

The process

Investigating this complaint against Perron could have gone down a couple of different paths.

If his comment was seen as a form of racial harassment, the city personnel department could have launched an investigation of its own, like it would do under similar circumstances in any other city department.

But in the police department there’s another route. When a member of the public complains about a police officer, the complaint is sent to the department’s Internal Affairs office, or IA, for an investigation.

And once IA completes its investigation, the report is handed over to an Independent Police Auditor who reviews the report and determines if the investigation was handled properly.

City Council created the Independent Police Auditor position in 2006 to provide more oversight of the police department.

HR investigations are never released to the public. There are several state laws that prohibit personnel matters from being disclosed publicly.

However, the Independent Police Auditor summarizes cases he’s reviewed in a semiannual report to the council, which is released to the public. Officers’ names are redacted from the reports.

It appears the complaint about Perron was handled as an HR matter, with an outside counsel investigating the incident, and then was later given to the Independent Police Auditor.

When the Post described the case to Stephen Connolly, a Los Angeles attorney who works on contract as the city’s independent police auditor, he contacted the police department because he hadn’t been aware of it. Connolly said in an email later that the allegation the Post described was addressed in the fall of 2017, and had been resolved.

“However, it did not come to us for review, apparently because it was not handled through the normal Internal Affairs investigative process,” Connolly said in an email. “Instead, the department and the city assigned the matter to an outside party.”

The police auditor’s role

After Connolly and his partner Michael Gennaco learned about Perron’s case, they found out that it wasn’t the only police investigation that had not been released to them.

The city’s HR director, Rumi Portillo, confirmed that she and Police Chief Bob Jonsen had realized that two HR cases involving police had not been released to the Independent Police Auditor, keeping them out of the public eye.

“There was not a clearly established internal protocol for reporting to the police auditor,” Portillo told the Post in an email. “The city manager’s office will be providing direction to HR in regard to a protocol for cases in the future.”

Portillo said that those two cases were the only ones her department had handled involving police officers in the past decade.

She noted that she determines whether internal police investigations handled by HR are investigated internally or sent to an outside investigator. HR cases involving city employees are not typically released to the public.

Gennaco said it is not unusual for investigations into the conduct of high-ranking officers to be handled by an outside party, such as an attorney hired by the city on contract.

The practice avoids the awkwardness of a sergeant or lieutenant investigating a complaint against his or her supervisor, he said.

“If the chief was the subject of an investigation, obviously an investigator within the department couldn’t do it,” Gennaco told the Post.

After Gennaco and Connolly found that the HR cases hadn’t been sent to them, city officials sent the cases to the auditors. Portillo said she was working with the chief and police auditors on “the procedure for future reporting.”

City officials and the police auditors have declined to reveal the outcome of the case, but more information is expected to be released to the public in the police auditors’ public report.

More cases to be revealed

Connolly said this month’s report would include more than one HR case that was either farmed out to an outside investigator or handled internally by HR.

He noted that in the forthcoming report, the auditors would recommend that the city release all of its internal investigations to the police auditors.

“The HR thing is new and we talk about how we hadn’t had those on our radar before and now we do, so that will be the protocol moving forward,” Connolly said.

It’s bad that Perron said this, but it’s even worse that the department covered it up for so long. Why is the City’s first instinct to hide bad news from the community?

I don’t think this is the kind of comment Captain Perron would have said. I’ve talked to him a couple of times over the years, and he doesn’t seem to be a racist or anyone who is overly angry or hostile to people. He seemed well adjusted and intelligent. I’m hoping this isn’t true.

As I understand it, the Independent Police Auditor was established by City Council to review all complaints and misconduct reports, and forward them to council and the public. It looks like the police bypassed that process to protect a high-ranking officer from public scorn. I’m also surprised that Perron was promoted after this incident.