BY BRADEN CARTWRIGHT

Daily Post Staff Writer

After a 20-month battle, the Palo Alto Police Department is unencrypting its radios to once again allow the public to listen in to police communications, acting Chief Andrew Binder announced yesterday.

The long fight for radio transparency spurred state legislation and united the publishers of the city’s two competing newspapers. A marathon council meeting didn’t result in any change, despite the mayor calling encryption a First Amendment issue.

In the end, a new chief made the difference.

By Sept. 1, Binder said Palo Alto will follow the model of the CHP, which protects personal information by having officers read only pieces of the information over their radios. Officers can also call the dispatch center on a cellphone, the department said in a statement.

Binder’s decision to unencrypt comes four days before City Council is scheduled to approve his permanent hire.

“I’ve taken a lot of things into account,” he said in an interview. “And I think it’s in the best interest of the community to do this.”

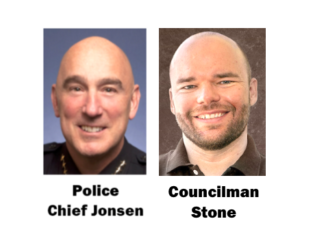

Councilman Greer Stone, who has been leading the push for unencryption, said yesterday that he was ecstatic about the change, and he is impressed with Binder’s leadership and fearlessness. He said this is a good example of public advocacy leading to positive change.

“Sometimes the road to doing the right thing can be windy and long, but I think we got it right here,” Stone said. “It’s a good day in Palo Alto.”

Retired Chief Bob Jonsen, who is now running for Santa Clara County Sheriff, encrypted Palo Alto’s digital radios in January 2021. He said he was following a memo from the state DOJ on Oct. 12, 2020, that told police to protect personally identifiable information, such as names paired with a drivers license number or a home address.

The DOJ gave agencies two options: create a policy to protect personal information, or encrypt their radios.

San Mateo County agencies kept their radios open. Their chiefs distributed memos to their officers that told them how to read information over the radio without disclosing personally identifiable information, and the DOJ signed off on the policy.

Santa Clara County agencies all went to encryption throughout 2020 and 2021. Los Altos and Mountain View followed Palo Alto a month after.

The public and media objected

Jonsen’s decision to encrypt was met with pushback from members of the public and the media. He made the change without any public discussion beforehand — a decision he later said that he regretted.

Encryption made it harder for reporters to go to an event, take pictures and talk to people about what happened. For example, reporters used to go out during storms and see which roads were flooded, where trees were knocked down and who was impacted.

Reporters could also go to crime scenes and talk to witnesses to get an independent account of what happened. Without open radios, none of that was possible.

Stone called on the rest of council to vote on the issue, and they finally had a discussion on April 4 this year.

Four days before the meeting, the executive director of an agency dedicated to radios in Santa Clara County wrote a memo to council members warning them about unencrypting.

Eric Nickel, head of the Silicon Valley Regional Interoperability Authority, said that Palo Alto could be left out of radio “talkgroups” — which are channels created for a specific purpose — with neighboring agencies and sued if its radios are unencrypted.

“No single agency in Santa Clara County is able to stand alone and handle all of their incidents without mutual aid,” Nickel wrote.

But at the same time, neighboring agencies in Menlo Park and East Palo Alto haven’t had issues with Palo Alto even though they remain unencrypted.

Warning was walked back

Nickel walked back his warning in a follow-up memo on May 12 to the Santa Clara County Police Chiefs Association. He said police departments could go either way and his agency would support them.

“Talkgroups will remain available to all members no matter their encryption status,” he said.

At the April 4 meeting, Shikada invited the publishers of two newspapers — Daily Post editor and publisher Dave Price and Palo Alto Weekly publisher Bill Johnson — to make their cases for open airwaves.

As the meeting went on past midnight, Stone made a motion to unencrypt — but the rest of council voted against him 6-1.

Jonsen argued that Palo Alto has the technology to encrypt its radios, so the department is required to do so to follow the state DOJ memo.

Stone said he strongly disagreed with Jonsen’s interpretation, so he wrote a letter after the meeting asking the author, DOJ division chief Joe Dominic, to clarify. Dominic said regardless of the technology, Palo Alto didn’t have to encrypt.

City Council has continued to stand behind Jonsen. Five council members endorsed him in the election for sheriff, while Stone endorsed his opponent, retired sheriff’s Capt. Kevin Jensen.

Stone wrote his own memo this summer calling for another vote in light of the clarification from Dominic, but now he said it looks like he won’t have to bring it forward.

More reforms

Stone said unencrypting may just be a first step, and Binder is open to more reforms toward accountability and transparency.

“This is a sign of him bringing that new perspective into the department and not being as traditional and careful as chiefs we’ve seen before,” Stone said.

Binder became acting chief on June 8. He said in an interview last week that ending encryption is a way to improve the police department’s relationship with the press.

“It’s one of the things that’s important to me, that I want to do as new chief of this community,” he said.

Ken Kratt, the president of the police union, said in an interview on June 1 that rank-and-file officers don’t care if radios are encrypted or not.

“We have no problems with people listening to us,” he said. “I’ve been pressing that button (on my radio) for 23 years. Whether its encrypted or not, I’m going to keep pressing that button. That’s just what I do.”

State legislation

It remains to be seen whether other Santa Clara County agencies will follow Palo Alto. There’s a bill in the state legislature, Senate Bill 1000, that would require police agencies to broadcast their communications by Jan. 1, 2024.

Sen. Josh Becker said he wrote SB1000 after seeing what was going on in Palo Alto. The bill is under review by the Assembly Appropriations Committee, which will announce its decision on Aug. 11.

The bill’s biggest challenge is its projected cost, which is a matter of dispute.

An analysis by consultants working for the Assembly Appropriations Committee said that reversing encryption would cost hundreds of millions of dollars.

But the cost analysis assumed that agencies would have to buy all new radios and equipment, and that’s not the case in Palo Alto: Capt. James Reifschneider said in an email yesterday that a radio technician has to re-sequence each radio so it’s easy for officers to get on an unencrypted channel, but the department won’t have to buy new radios.

Becker said SB1000 would actually save the state money by making it clear that agencies on analog radios, which can’t be encrypted, don’t have to purchase digital radios. For example, Becker said San Bruno was talking about going to a digital system to encrypt for $5 million, and his office clarified that it wasn’t necessary.

Stone said he hopes that Palo Alto’s move will show other cities and the Assembly that unencryption can be done at a low cost. The timing of the change is ideal, he said.