BY DAVE PRICE

Daily Post Editor

The dispute over the decision by Palo Alto, Mountain View and Los Altos to encrypt their police radio frequencies may just boil down to misreading of a memorandum.

We’ve all read a document and thought it meant one thing, and then, upon further review, realized it means something completely different.

I think that’s happened here. When Palo Alto police encrypted their radio frequencies last month, Police Chief Robert Jonsen said he was following a “mandate” from the state.

The mandate, he said, was spelled out in a two-page memorandum dated Oct. 12 from the state Department of Justice’s Information Services Division, which maintains the state criminal database known as CLETS or the California Law Enforcement Telecommunications System.

The memo, by Information Services Division Chief Joe Dominic, cites longstanding federal and state policies about keeping personally identifiable information and criminal justice-re-lated information confidential. None of those policies were new. And no state law has been passed mandating encryption. So the impetus for this memo wasn’t clear. The Post tried to interview Dominic but he wouldn’t take our calls.

Two choices

But in the memo, at the top of the second page, it says “compliance with these requirements can be achieved using any of the following.”

That’s followed by two bullet points.

One bullet point says a police department has the option of encrypting its police radio signal.

The second bullet point says a police agency can establish a policy that would protect such information without encryption.

“This will provide for the protection of CJI (criminal justice information) and PII (personally identifiable information) while allowing for radio traffic with the information necessary to provide public safety,” Dominic wrote in the memo.

It’s incorrect to say the police department is following a “mandate” to encrypt its radio signals. An accurate statement would be that the department had a choice, and picked encryption over public broadcasts.

Chief Jonsen had a choice. Maybe he didn’t know it, since he’s saying he was following a mandate to encrypt.

We’ve all misread documents. I’m willing to give him the benefit of the doubt.

Maybe he didn’t like the second choice and disregarded it. The second option could be achieved a number of ways. Officers can obtain and send information by picking up their cell phone and calling the dispatchers, something they’ve been doing for years. Or they can communicate with text messages. Or the department can set up a separate encrypted channel, like Los Altos has been using for a number of years.

It’s your police department

As we’ve stated before, the public has a right to know what its police department — an agency funded with its tax dollars — does on a real-time basis.

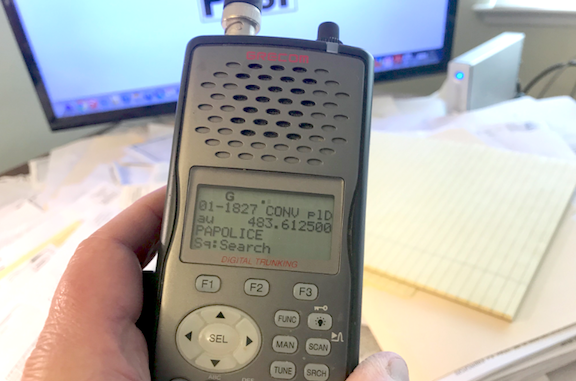

Police and fire departments have dispatched their officers over the air without encryption since the 1940s.

Two weeks ago, we were hit with a major wind and rain storm. The Post’s typical procedure on such an evening is to monitor the police scanner for trouble — like a tree crashing into a house or a flooded highway — and send a reporter to the scene to take pictures and conduct interviews. Now that our police scanner is silenced, we weren’t able to do that. The real loser here is the public. They get less information and the police get to keep more secrets. So much for all that talk about transparency.

Chief Jonsen and his counterparts in Mountain View and Los Altos have decided to encrypt without bringing this public policy decision to their respective city councils.

I think one of the reasons why law enforcement is under fire in America today is the lack of civilian control. City councils across the country have been content to allow their police departments set their own policies without any civilian oversight.

Time for council to get involved

Yet I would argue that city council members need to become engaged in their police departments. They need to understand how they work, the influence the police unions have and the policies or “general orders” of their department. Council members need to dive into this if they want to have any oversight of their police.

A city’s police department is a potential source of multi-million-dollar liabilities. A city gives its cops guns, Tasers, fierce dogs, high-powered vehicles and the authority to arrest people and search their belongings. If they get anything wrong, the city has to dole out millions of dollars to plaintiffs and their lawyers. Palo Alto has written some embarrassing checks in the past year to settle police brutality suits. One would think that after signing the first half-million-dollar check, council members would start paying close attention to how their department is run. After the second check, a council member would be negligent if they ignored this responsibility.

If council wants to take control, a good place to start would be by restoring the police radio frequencies to the public.

Editor Dave Price’s column appears on Mondays. His email address is [email protected].