BY ALLISON LEVITSKY

Daily Post Staff Writer

Just in time for Star Wars Day — May the Fourth be with you all — scientists at Lockheed Martin opened their labs to the Post to show off their work, from a space telescope to search for Earth-like planets to a “proton gun” chamber that simulates the conditions of outer space.

Much of the work at Lockheed’s Stanford Research Park facilities, where about 500 scientists, technologists and engineers are employed, focuses on space research. Primary clients include NASA and the Department of Defense.

Lockheed has been operating at Stanford Research Park since 1956 and is on a 100-year lease. Some 3,000 more scientists work at the Lockheed Martin facility in Sunnyvale, which does more spacecraft production and large-scale testing.

Space telescope

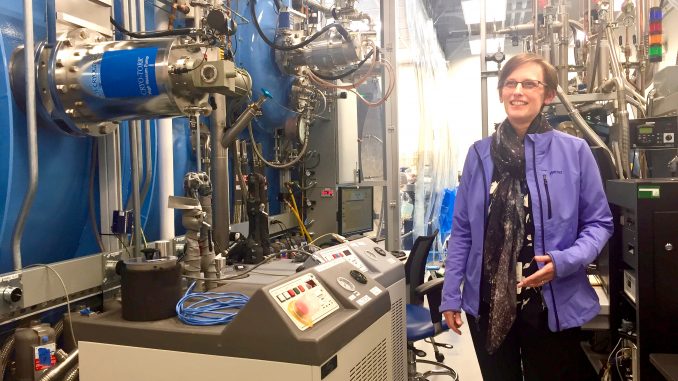

Senior Manager for Astrophysics Alison Nordt leads the team of 200 that developed the Near Infrared Camera or NIRCam on the James Webb Space Telescope, the more powerful successor to the Hubble Space Telescope.

The Webb telescope, which cost $9 billion to build, is set to launch into space 1 million miles from Earth in March 2021.

NIRCam will be Webb’s primary imager, detecting light from the earliest stars and galaxies, stars in nearby galaxies and young stars in the Milky Way and Kuiper Belt.

The camera’s coronagraphs allow astronomers to capture images of faraway planets by blocking the light of a brighter object nearby — that planet’s sun.

This allows scientists to search for planets that may be just far enough from their sun to support life, with oxygen and liquid water.

“We really want to find an exo-Earth,” Nordt told the Post.

But Nordt said that at this point, the only reason to look is “human curiosity.” Scientists can’t conceive of a future generation in which it would be possible to send a human population to such a planet.

“We’re never going to get there,” Nordt said.

Spotting lightning

A technology with more immediate consequence for earthlings can be found in the Geostationary Lightning Mapper or GLM, a single-channel, near-infrared optical transient detector that can spot lightning all over the Americas and adjacent oceans.

Think of it as a large, high-speed video camera that captures 500 frames a second, GLM Chief Scientist Samantha Edgington said.

Some 97% of the flashes of light the instrument picks up aren’t lightning. Using computer algorithms, the instrument is able to weed out the noise and show researchers where the lightning is to track thunderstorms and tornados.

Data processing in space

The instrument processes the images on board because it’s too difficult to send that much data down to Earth.

In some cases, accurate weather forecasting can be a matter of life and death, Edgington said.

Edgington’s team is working on building the third and fourth version of the GLM. The first two GLMs are currently in use on satellites operated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA.

NOAA’s Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites circle the earth from about 22,300 miles away.

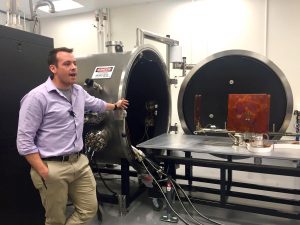

All of these instruments Lockheed builds need to be proved to be space-worthy before they can be launched. For that reason, Lockheed has two atomic particle accelerators that simulate radiation and plasma particles for objects inside the chambers, which create a vacuum and neutral environment.

High-speed accelerators

Senior Research Scientist Dave Knapp said the conditions imposed inside the accelerators can vary because depending on where an instrument is in space, conditions will vary. Temperatures can shift widely as a satellite orbits around the Earth.

The accelerators can sometimes be activated for months at a time. That allows scientists to check on equipment at intervals throughout the acceleration process, which can inform them of how space conditions will affect them over a long period of time.

The particle accelerators speed protons to more than 12 million miles an hour, or 2% the speed of light.

Editor’s note: The story was corrected to replace the term “proton guns” with the more accurate description “particle accelerators.”