This story was originally printed in the Daily Post on July 8.

BY ELAINE GOODMAN

Daily Post Correspondent

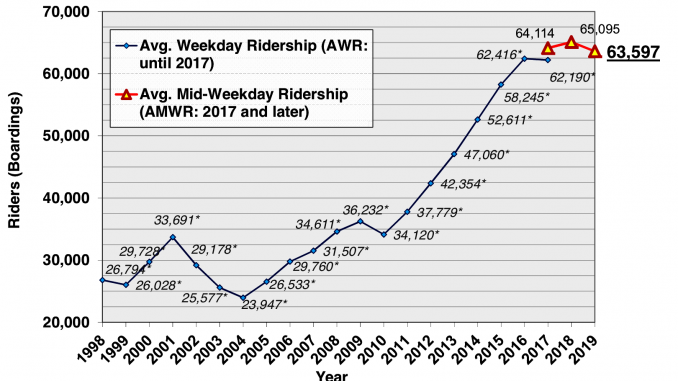

Midweek Caltrain ridership has dropped 2.3% this year compared to last year, according to newly released figures that come after the commuter railroad reported weekday ridership decreases for six months in a row.

The new numbers, based on a headcount of passengers early this year, show 63,597 daily midweek boardings compared to 65,095 in 2018.

The numbers, which will be presented to the Caltrain board of directors on Thursday (July 11), are used for evaluating possible service changes.

“Caltrain is very dependent on fare box revenue, with approximately 70% of its revenue coming from ticket sales, so any decrease in ridership is a concern,” San Mateo County Supervisor Dave Pine, who sits on the Caltrain board, said Sunday.

Pine said overcrowding is one factor that might be contributing to a decrease in midweek ridership.

“Many trains carry far more passengers than their seating capacity, and this may discourage riders,” Pine said in an email.

Shuttle driver shortage

In addition, Pine said, some shuttle routes are being dropped due to a shortage of drivers, which might decrease ridership. The shuttles take passengers from Caltrain stations to destinations such as business parks and medical centers.

Fare increases may also be playing a role in midweek ridership decreases. Monthly pass rates went up in October. But Pine noted that participation in the Go Pass program has increased despite a price increase from $237.50 to $285. Caltrain’s Go Pass program allows companies, educational institutions and residential complexes to buy annual unlimited-ride passes for workers, students or residents.

Each year in January or February, Caltrain conducts a headcount of passengers. In past years, Caltrain counted passengers on all five weekdays, Monday through Friday. But last year, Caltrain changed its method to counting passengers on two days in the middle of the week, Tuesday, Wednesday or Thursday. The change was due to “increasing costs and budget constraints,” Caltrain said.

The figures reported from the annual headcounts are the number of boardings, and therefore riders are counted once when they depart for a destination and again when they return. So the number of riders is approximately half the number of boardings, or roughly 31,798 as of early this year.

Heaviest ridership times

Ridership figures from this year’s headcount were also broken down by time of day. “Traditional peak” travel — in which riders head north during morning rush hour and south during evening rush hour — accounted for 54% of midweek boardings. The number of traditional peak boardings was relatively flat compared to last year, increasing 0.5%.

Reverse peak boardings, where riders go south during morning rush hour and north in the evening, made up 30% of boardings and decreased 7.2% compared to last year. Evening ridership on midweek days saw the biggest drop, falling 16.4%.

But mid-day boardings, outside of rush hours, actually increased by 5.5% on midweek days.

In addition to the annual passenger headcounts, Caltrain provides monthly ridership numbers to its board of directors. Those figures are based on ticket sales and adjusted using ridership models, Caltrain said on its website. The annual passenger headcounts are used to help calibrate the monthly ridership numbers.

Monthly ridership reports have shown six straight months of decreases in weekday commuters compared to the same month a year earlier. Average daily weekday ridership fell by 4.3% in October, 5.2% in November, 4.2% in December, 2% in January, 3.6% in February, 1.7% in March, and 1.9% in April.

Chief Operating Officer Michelle Bouchard listed some potential reasons for the decreases while discussing monthly ridership numbers with the board in April. Those included very wet winter weather, fare increases, trains reaching their capacity at peak periods, and overall economic cooling, according to minutes of the meeting.

The questions about ridership come as Caltrain is in the midst of an $2 billion electrification project for the rail line. Caltrain says electrification will allow it to provide more frequent and potentially faster train service, and increase its capacity initially by more than 30%.

Trend reversal

The recent slowdown in weekday ridership is in contrast to past trends. Caltrain’s average weekday ridership grew rapidly over a six-year span, from 34,120 boardings in 2010 to 62,416 in 2016, increasing roughly 10% a year. But the growth stopped abruptly after that, with boardings staying relatively flat in 2017, rising 1.5% in 2018, and dropping 2.3% this year.

It might be time to put these costly grade separation projects on hold until we see evidence of the need to expand Caltrain.

Monthly passes used to be 23.5 x daily pass. Now they are 30 x daily pass. Caltrain Gouging riders? YES.

http://www.caltrain.com/Assets/_MarketDevelopment/pdf/Caltrain+Fare+History+thru+2019.pdf

Caltrain’s capacity issues, depicted by Michelle Bouchard and other Caltrain staff as contributing to fewer passengers using Caltrain during commute times, was used consistently during the past year when Caltrain staff ignored overwhelming public requests to change the layout of the electric cars anticipated in 2022 so as to make the layout more accommodating for passengers with large items such as strollers or bikes, flexible use space that would increase capacity by providing more standing room space options during special events or commute hours. Bike capacity has been capped by Caltrain staff during the recent passenger decline and has likely resulted in much of the decline in train use during commute hours and the 5% increase in off-peak usage, since passengers with a bike are not permitted to board full bike cars and tend to drive in order to have a more reliable way to get to/from work on time. Caltrain will have a hard time getting approval from the voters in San Francisco, San Mateo, and Santa Clara counties for their proposed tax increase in 2020 with plummeting rider numbers and a board of directors so tone deaf to the members of the community who rely on Caltrain to commute.

The excuse that overcrowding is leading to a ridership decline is a pile of crap. If the train is too crowded, you just take another train. How often are we told that Caltrain serves people who don’t have another way to get around? Yet if the too-crowded argument is correct, then people must have lots of choices for commuting. I guess that’s what passes for logic at Caltrain these days. What a joke.