OPINION

BY DAVE PRICE

Daily Post Editor

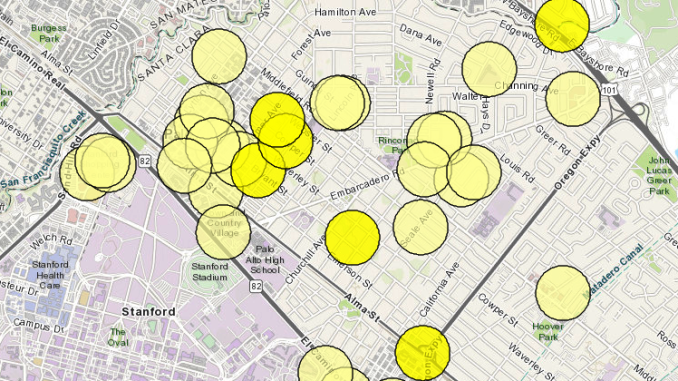

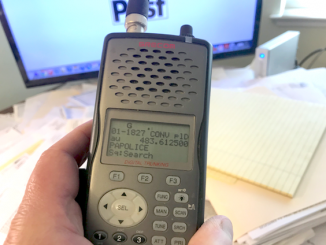

A year after Palo Alto Police Chief Robert Jonsen decided to encrypt police radios — making it impossible for the public to monitor police activities on a real-time basis — he has unveiled the Beta Police Calls for Service Interactive Map. In a press release, the police say this is a “better alternative to monitoring police radio scanners.”

That’s absolutely wrong.

1. With a scanner, the public knows about the incident the same time officers in the field learn about it. With this map, information about an incident is posted only after it ends. By that time, the witnesses will be gone. This makes it impossible for the press to get an independent account of the incident. Instead we have to rely solely on the police department’s version of events. For a department with a documented history of covering up police brutality, this isn’t a good idea.

2. The information about the police calls is vague. It doesn’t say what happened, where it happened or how police responded.

3. The circles on the map that identify incidents are so large, you can’t pinpoint where something happened.

4. When a user clicks on a circle, the information that comes up is meaningless. What does “MedInfo” mean? An ambulance run? A 5150? A kid with hiccups?

Like the decision to encrypt, the development of this map was done without any discussion with the community, especially the end-users.

Instead of this interactive map, the city should have gone back to un-encrypted police radio frequencies, and taken the same approach as the CHP, which broadcasts without encryption.

What is the CHP alternative?

In October 2020, the state Department of Justice’s police data operation put out a memo to all local police departments telling them to either encrypt their radios or find other means to protect personal information.

Many in law enforcement took this memo as a mandate to encrypt. That was false.

The memo gave departments a choice. Palo Alto went for the most extreme, anti-transparent choice — encryption. But the CHP, which for technical reasons can’t encrypt on all of its frequencies, came up with an alternative that’s acceptable to the Department of Justice.

Here’s how it works: When a CHP officer wants dispatchers to check someone’s driver’s license number for information such as whether the license is suspended, the officer will give the license number over the radio and the dispatcher will read it back to make sure they’ve heard it correctly.

When the dispatcher responds to the officer with the results of the driver’s license check, they can give either the person’s first name or last name, the driver’s license number and the license’s status. That prevents transmission of someone’s full name and their driver’s license number at the same time.

Additional information such as address, date of birth, and physical descriptors would only be provided when requested.

The CHP alternative is a simple system that doesn’t cost any money to implement and is perfectly legal.

Transparency reduced

Encryption isn’t the only way Jonsen’s department is reducing transparency. Police have decided that reporters can no longer call police to find out more about crimes — all questions must go through the police information website. And, in the last couple months, the information on the police blotter has been greatly reduced.

Blotter’s history

The police blotter began in 1997 due to public outrage over the horrific murder of NASA scientist Bert Kay on Gilman Street. That brutal killing led to a town hall meeting where residents demanded that the police and city council provide more information to the public about crimes. Kay’s killers were repeatedly arrested and released, and each time their crimes became more violent. Yet the incidents weren’t publicly known, which angered people. At the end of the meeting, then-City Councilwoman Liz Kniss and the police chief, Lynne Johnson, asked me if I’d be willing to print a police blotter. Of course I agreed. Soon other mid-Peninsula police departments began to offer their blotters to us.

Last month, Palo Alto police decided to reduce the amount of information in the blotter. And, again, the changes were made without any consultation with the community or end-users.

1. We used to get more incidents. The logs are now shorter than they used to be, and the information is a number of days old.

2. The new blotter is vague. It is difficult to tell what is being reported. For instance, the Jan. 19 log says “Hit and run resulting in death or injury.” There’s a big difference between the two. Did the victim go to the morgue or the hospital?

3. The new log doesn’t have details about incidents like the old one did. What was stolen? A purse? A bike? A garden statue?

Talk to reporters

It used to be that reporters could call police directly and find out about a particular incident. Now if a reporter has a question, it has to be entered into a portal on the police website. Sometimes a reply will come the same day, sometimes it takes days.

In some law enforcement agencies, the boss makes it his job to talk to the press every day. An example is longtime San Mateo County District Attorney Steve Wagstaffe, who emails a memo to the media nearly every morning giving the status of various newsworthy cases. Then, in the late afternoon, he takes calls from reporters to answer their questions about what happened that day in cases they may be following.

You’d think that if Wagstaffe can do that every day, the Palo Alto police chief could do the same. It would allow the chief to keep daily tabs on ongoing cases with his officers so that he would be up-to-speed when he answers questions from the press. And getting to know the reporters by talking to them every day, he would have more comfort in dealing with the press. Sometimes I’ve found that police officers, who are extraordinarily brave in most circumstances, become unusually nervous around reporters.

Palo Alto City Council should restore police transparency by taking the following actions: (1) order police to un-encrypt their radios and use the CHP alternative, (2) restore the police blotter to its pre-January 2022 level of information, (3) allow officers to speak directly to reporters again.

Chief Jonsen, a candidate for sheriff, has given the city notice of his retirement. Council shouldn’t wait until he’s gone to make these changes. This is a matter that has festered over a year and should be at the top of council’s agenda immediately. The public has every right to know what its police department is doing.

Sidebar: Why police radios matter

For 70 years, people have been able to use police scanners to listen into their local police and firefighters as a way of knowing what’s going on in their community. It’s a check-and-balance on law enforcement.

For news organizations, it allows reporters and photographers to get to the scene of an accident, fire, explosion, shooting or other newsworthy event quickly, so they can see for themselves what happened and bring the story to you.

With encryption, police agencies tell reporters what happened long after the event has ended.

For instance, on a stormy night last year, trees were crashing down, power lines were falling and there was flooding in different parts of Palo Alto.The typical procedure in this newsroom is to send a reporter out on the road with a police scanner and a camera to document what happened. In the next morning’s paper, the reader gets a report on the damage the storm did in town, such as the trees that smashed through houses or cars, the flooding and the fires.

But with encryption we weren’t able to do that story because our scanners were silent. Encryption eliminated the news you were able to read.

Some people have argued that criminals listen into the scanners to get the personal information of people contacted by police. Others argue that criminals will use the police radio to avoid detection.

To test those theories, we submitted requests with Palo Alto, Los Altos and Mountain View for all such cases. None of the cities had anything. It doesn’t happen.

I appreciate the explanation as to how police have been reducing transparency in the past couple of years. I think people at the City lose sight of the idea that the press is merely an extension of the public. Reporters ask questions on behalf of the public. Cutting off communication with the press is really cutting off communication with the public. I hope council members can address this problems sooner than later. We’re lucky to have devoted reporters who work hard to bring us the news. The City should cooperate with them and not make it harder to get information to which the public is entitled.

OMG, Dave mentioned Wagstaffe. I think Wagstaffe is an honest DA but whenever his name comes up there are these trolls who believe in conspiracy theories and black helicopters who will suddenly appear. It’s fun to watch them spin lies every time Wagstaffe’s name is mentioned.

Every time i read something written by these trolls, I hum the song to the X-Files!

Thank you very much for addressing this subject, as a fellow video journalist in the bay area, I agree with you %100.