BY SARA TABIN

Daily Post Staff Writer

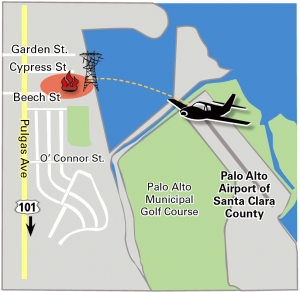

Around 8 a.m. on February 17, 2010, multiple 911 calls began coming into the Palo Alto Police Department from people on the border of Palo Alto and East Palo Alto.

A plane had crashed onto Beech Street in East Palo Alto. One witness would later say the crash felt like an earthquake from the ground. Some people even said the plane had exploded, according to current Palo Alto Office of Emergency Services Chief Kenneth Dueker, who was on duty that morning.

The plane hadn’t exploded, but a power tower had. That’s because the plane had cut across the city’s power lines. After the explosion, Palo Altans were without power for 12 hours.

Dueker’s day began at 6 a.m. but it wouldn’t be over until midnight.

It’s possible that Dueker’s long day could happen again if a similar event knocks out the city’s power lines.

That’s because the city, which delivers power to homes and businesses, hasn’t built a backup system to bring power into Palo Alto.

Palo Alto and the Menlo Park Fire District, which serves East Palo Alto, help each other out in disasters, so Palo Alto immediately sent first responders across the San Francisquito Creek to the scene.

Dueker said the crash site was complex. The three men that were on board the plane, all Tesla engineers, were dead. They were Brian Finn, 42, of East Palo Alto and Andrew Ingram, 31, of Palo Alto, and Pilot Doug Bourn, 56, of Santa Clara.

Dueker said the crash site was complex. The three men that were on board the plane, all Tesla engineers, were dead. They were Brian Finn, 42, of East Palo Alto and Andrew Ingram, 31, of Palo Alto, and Pilot Doug Bourn, 56, of Santa Clara.

First responders had to deal with multiple fires and hazardous chemicals leaking from the plane to make sure more people didn’t get hurt. One wing from the plane had hit a daycare center. Fortunately, only one child had been dropped off for the day and no one was seriously injured. One woman was taken away in an ambulance for high blood pressure.

Dueker said 8 a.m. was a convenient time for an accident because the department was well staffed. He said that while police officers were dispatched to the scene of the crash, detectives who would otherwise work in the office were put on patrol duty. Palo Alto also asked Mountain View and Los Altos for backup with things like burglary alarms.

Police and firefighters put out the fires and used a substance like kitty litter to stop jet fuel from leaking into storm drains.

Dueker said they also had to make sure people didn’t try to get back into houses where there might be smoldering airplane pieces.

“People wanted to run in and get their computers out of their house,” he said.

“No, you’re going to wait because it’s not worth your life,” Dueker recalled saying to frantic residents.

First responders couldn’t clean up everything because they had to preserve the crash scene as much as possible so that federal agencies could investigate the crash later on.

“Surviving family members want to know why their loved ones are dead in a crash,” he said.

The National Transportation Safety Board ultimately said the crash was caused by pilot Doug Bourn’s failure to gain enough altitude to clear the power lines. The board’s report says that the plane took off even though an air traffic controller said he could not clear the plane for takeoff because of low visibility. The controller told Bourn that takeoff would be at his own risk.

Long day to come

The scene was stabilized without further problems within an hour, but that was only the start to a very long day for Palo Altans.

The plane crash had cut the three lines that bring power to Palo Alto from PG&E’s grid.

All three lines come into Palo Alto through one corridor on the bay side of the city near the airport.

That means that when the 5,500-pound twin-engine Cessna 310R hit the 80-foot-high power line, it knocked out the city’s only power source.

Dueker said the city’s biggest concerns were whether hospitals and people who rely on electric medical devices would have enough energy.

He said there was a lot of anxiety in the community as people’s Wifi and cell service started to fail. He said cell towers don’t have a lot of back-up power during an outage.

“It would probably be even worse today because people are clinically addicted to their social media and constantly being connected,” he said.

The city dispatched emergency service volunteers, who are given walkie-talkies, to check on their neighbors. He said the city has over 600 volunteers now, more than the couple hundred it had in 2010, but the city is always looking for more.

Nobody ended up injured from the outage, but Dueker said a few people were stuck in elevators and Stanford Hospital had some trouble with its generator. Small businesses also suffered, especially restaurants where thawing freezers can mean spoiled food.

Traffic lights in the city stopped working. Police set up traffic cones and stop signs at intersections and then trusted drivers to work out the situation. There were eight car crashes by midday but no serious injuries, according to a 2010 statement from Lt. Sandra Brown.

Dueker said there was concern during the day that the outage could last weeks or even months because the tower exploded.

“Many of us on staff were surprised to hear that a sophisticated city like Palo Alto had one power line into the city,” he said.

Menlo Park Fire District Chief Harold Schapelhouman was also shocked when he heard that power was gone in Palo Alto. He called it a “twist” in an already difficult situation.

On the ground, there were traumatized residents who had to flee burning houses, cars on fire and the deaths of the three men from the plane.

A few hours after the crash he got a call from Palo Alto Fire asking that his team not block PG&E’s access to the power lines because workers needed to get in to restore power for the city. Until that call, Schapelhouman said he had assumed that some homes had lost power but PG&E would be able to reroute the power from other parts of the city.

Power was ultimately restored to the city after only 12 hours because PG&E workers had a pre-assembled power tower flown in using a helicopter.

Schapelhouman said the helicopter had to navigate the same thick fog that downed the airplane as the chopper came over the mountains from the Central Valley where the backup tower had been stored.

“They barely made it in before sundown,” he said. “They couldn’t fly that mission if they didn’t get it in before dark.”

What’s changed?

It’s been a decade since the crash but Palo Alto’s energy situation hasn’t changed much. The city is still powered through the sole line that comes from under the Bay.

City Manager Ed Shikada said Palo Alto was looking at making a connection with Stanford’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in San Mateo County as an alternative energy source, but the university recently informed the city that it’s no longer interested in the partnership.

Shikada said Palo Alto has looked into the idea of a second power line from PG&E to the city substation at Colorado Avenue and W. Bayshore Road. That would cost about $200 million. The city has also looked into connecting to PG&E’s Ames substation in Mountain View but no cost has been estimated for that idea.

Palo Alto is also interested in trying to make a “micro” energy grid in the city using solar panels and battery storage that would allow the city to have some self-sufficiency in case of an emergency.

Dueker said the problem with investing huge amounts of money into a second power line is that Palo Alto would still be left vulnerable if PG&E’s grid was damaged.

He said a microgrid would give the city more resiliency even if it is only generating enough power for critical city locations. He said solar panels on rooftops throughout the city could feed into a backup power system.

Dueker said many people think they are protecting themselves from power outages by installing solar panels. Solar might be good for the environment and utility bills, but the panels themselves won’t be useful if the grid is down since solar panels in Palo Alto feed into the power grid. Dueker said solar panels usually turn off if the grid is down for safety reasons. People need a battery system if they want to store energy.

New tech

Spokeswoman Horrigan-Taylor said the city has acquired a mobile operations center vehicle. The RV-sized vehicle runs on solar and would let OES keep working through an electrical failure caused by storms, accidents or cyber-attacks on the electric grid.

Palo Alto also has access to the NASA Ames’ Aircraft Rescue and Fire Fighting vehicle which was added to the Santa Clara County Mutual Aid System since 2010 to fight aircraft fires.

Although there are more first response tools, there might be fewer first responders depending on when a disaster occurs.

Dueker said first responders are living further and further from the city as housing prices go up. He said that could be an issue if something goes down at 2 a.m. and most of the city’s firefighters and police officers are on the other side of the Bay.

“I’m one of the only first responders that lives here so I’m going to be lonely,” he said.

Flight regulation over East Palo Alto

Schapelhouman said he thinks there should be more regulation for air traffic over East Palo Alto. He said there is a lot of air traffic in a small area because of planes from airports in San Francisco, San Jose, San Carlos and Moffett Field as well as Palo Alto.

The 2010 crash took place in the fog like the helicopter crash that killed basketball star Kobe Bryant and eight others last month, said Schapelhouman. He said people shouldn’t be allowed to take off in foggy weather unless they have some sort of permit verifying that they have the skills to fly in difficult conditions.

He also said flights should go further down along the Bay to avoid flying over East Palo Alto. He said other flights before and after the 2010 crash have landed in the Bay, and the Fire District has sent out boats to help, but there is always the chance of a plane going down over a residential area.

Schapelhouman said the Fire District raised those issues after the 2010 crash but they haven’t been resolved.

Palo Alto residents have complained to City Council in recent months that they don’t want planes from San Francisco flying over their homes because of noise and air pollution.

The ‘miracle on Beech Street’

In spite of everything, Schapelhouman calls the crash the “miracle on Beech Street.”

“We lost those three people in the plane but no one else died,” he said. “It could have gone either way in a few instances.”

If it had happened a few hours later there would have been children in the daycare center. He said there were pieces of the plane’s fuller tank and landing gear everywhere and in trees and bushes that fell onto houses.

“It was amazing what the debris field looked like,” he said.

Palo Alto Utilities routinely runs a $20,000,000 ANNUAL surplus from over-charging us. How about either giving refunds and/or fixing problems like this?

Also, what’s happening to the lawsuit against PAU for these over-charges? Please do a follow-up article since we no longer have an in-house auditor.