GUEST OPINION

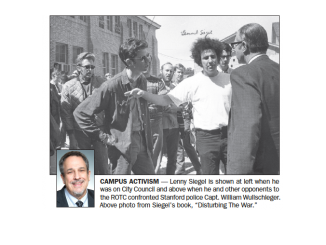

BY LENNY SIEGEL

East Palo Alto’s leaders aren’t the only ones who believe that Palo Alto and other slow-growth communities need to “step up” and plan for substantial residential development within their boundaries. But proposed state legislation to obviate local control, such as Senate Bill 50, is not the way to get it done.

Silicon Valley’s job-rich communities need to build more housing for many reasons. By driving up housing costs, our housing shortage is creating hardship for many people who work or have retired here. The high cost and low availability of housing is making it difficult for both the private and public sectors to attract and retain low- and middle-income workers, from restaurant workers to teachers.

The highly visible automotive commute of the vast numbers of local employees who drive more than an hour each way every day not only congests our roadways, it is our region’s number one source of climate-changing greenhouse gas emissions.

Even long-time homeowners are finding that it’s difficult for their grown children and grandchildren to live nearby. And the cities that house more workers than work there, such as East Palo Alto and San Jose, are stuck providing services with inadequate tax revenue.

About SB50

So it’s no surprise that people genuinely concerned about our housing crisis have joined the corporate backers of regional government to support top-down state legislation such as state Sen. Scott Wiener’s SB50, which would require cities to accept denser residential development proposals than they would approve on their own.

SB50 is a moving target. In response to criticism and to win votes in Sacramento, it continues to undergo changes, some of which may make the legislation less problematic. Furthermore, the language is subject to interpretation. However, SB50 is fundamentally flawed in two ways.

First, it takes a one-size-fits-all approach. For example, in originally emphasizing housing near transit, it ignored the fact that many cities don’t have respectable public transit in areas where housing should be built. Both Cupertino and Mountain View’s North Bayshore Area barely have any public bus service. Now it includes “job-rich” areas, but those are not clearly defined. I don’t see how state legislators can figure out, in advance, where dense housing should be built in every city covered by the legislation.

As I read the legislation, it focuses on property already zoned for housing. However, to protect existing neighborhoods and naturally affordable apartments, Mountain View is zoning commercial properties for housing, not properties already designated residential. This strategy should make it easier for people to walk or bike to work, or simply to drive less.

There’s more to it. Mountain View is designing medium-density, mixed-income neighborhoods in what have long been shopping areas and office parks, complete with housing, jobs, parks, schools, retail, and transit. Palo Alto could do the same, building complete neighborhoods in the Stanford Research Park, Stanford Shopping Center, and the industrial area east of San Antonio that everyone thinks is in Mountain View. Nothing in SB50 encourages this approach.

Tying the hands of cities

Second, it limits the ability of local governments to address how housing is built. Some of the concerns that housing skeptics raise are valid: traffic, parking, provision of schools, and ensuring that other services are made available.

So when Mountain View approves or plans for housing, it places conditions on development and requires community benefit funding in exchange for added density. It determines, on a case-by-case basis, which residential projects can manage with minimal parking.

The proponents of SB50 say that cities would retain much of their leverage, but if that were the case recalcitrant city councils could simply use that authority to block development, or at least tie it up in court.

To get housing built in North Bayshore, Mountain View found that it had to negotiate park and school funding requirements to balance public needs with developers’ financial requirements.

Mountain View is building a steady stream of both market-rate and subsidized housing. There is widespread support for housing precisely because the city, after consulting with residents, determines where and how it will be constructed.

If cities are forced to accept projects that don’t address neighborhood concerns, one can bet that there will be a backlash that limits growth in the long run.

Alternatives

Finally, there are other things that the state can do to promote housing growth in our area. It can provide funding for transit, road improvements, and school construction to communities that build their share of housing, as well as money to build subsidized apartments. Such a strategy not only would provide incentives for cities to address the housing crisis, it would create better communities.

Lenny Siegel served as Mayor of Mountain View in 2018 and was a member of City Council from 2014 to 2018.

This is welcomed, rational, long-term thinking in sharp contrast with desperate, irrational leadership in our state senate. Now the challenge is up to local city councils leaders to seize opportunities outlined by Lenny Siegel. Failure to act proactively will be costly.

SB50 is a disaster all around and will destroy the last vestiges of democracy we have left. No housing shortage is worth giving up local control and certainly not for this one-size-fits-all approach by Weiner and the YIMBY-bots. We will decide what gets built in our cities and towns and we will determine our future.

Lenny, well said! The only thing I would add is that we need more housing for middle income people. We have lots of “affordable housing” for the poor and lots of luxury condos for people who can pay $10,000 a month, but little is done for the middle income people.

So, the cities are doing unbelievably horrible jobs. Palo Alto is easily one of the worst, but we should just believe they are going to do better because they say so, even though they’ve said that for many years. I think SB50 is great. The only unfortunate part is that it doesn’t go far enough.