BY ALLISON LEVITSKY

Daily Post Staff Writer

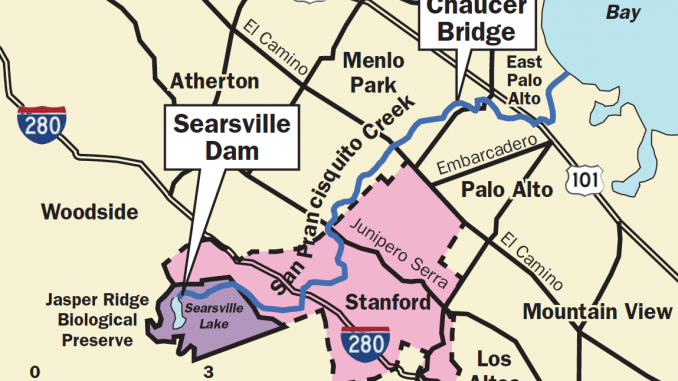

Replacement of the Pope-Chaucer Street Bridge — which was blamed for much of the damage in the 1998 flood that inundated Palo Alto, East Palo Alto and Menlo Park — could be delayed by a bureaucratic snafu between the San Francisquito Creek Joint Powers Authority and the San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board.

In the Feb. 3, 1998 flood, debris and vegetation became clogged in the bridge, which caused water to back up and overflow the creek banks, flooding neighborhoods on both sides.

The creek authority plans to replace the bridge with one that doesn’t have concrete blocks that constrict the flow. Currently, so much sediment is built up at the bridge that there are large trees growing out of it, said Len Materman, the creek authority’s executive director.

Creek authority leaders are currently studying the environmental impacts that the project would have in accordance with the California Environmental Quality Act.

But on Jan. 18, the water board sent a letter to the creek authority, urging them to take into account the expected increase in sediment loads flowing from Searsville Dam, a 65-foot masonry dam on Stanford lands upstream in the foothills.

Searsville Dam has been causing sediment to build up in Searsville Lake since the dam was built in 1892. It’s expected that the sediment buildup will start to flow over the top of the dam into San Francisquito Creek in the next decade or two.

Endangered species

The dam is said to harm the threatened steelhead trout population by blocking the fish from migrating upstream, prompting a lawsuit from two environmental groups in 2013 over alleged violations of the Endangered Species Act.

The lawsuit was stayed, but a court order required Stanford to address issues caused by the dam, by removing it or otherwise. In 2015, the university decided to open the bottom of the dam to release the sediment, but that project hasn’t been proposed to the water board.

Materman said that because the Searsville project is still at such an early stage, he doesn’t see it as his agency’s responsibility to plan for those future effects.

“They can’t require us to do that. No one’s required to mitigate for anyone else’s work,” Materman told the Post. “We’re working with Stanford, so that our science is consistent with theirs.”

Materman said the planned flood abatements, referred to as the Upstream of 101 project, wouldn’t make the sediment issue worse. The project takes into account the natural increase in sediment flow expected to come over the dam in the next 20 years, but doesn’t take into account the sediment flow that will come under the dam when Stanford opens it up.

The state Environmental Quality Act requires government agencies sponsoring projects to consider reasonably foreseeable future impacts, which water board leaders argue would include the Searsville project.

Another roadblock

Keith Lichten, chief of the water board’s Watershed Management Division, said that whether or not the creek authority is legally obligated to analyze the impacts of the Searsville project, “from an engineering perspective, it makes sense.”

Lichten maintained that the impacts of the Searsville project would be predictable enough for the creek authority to plan for them.

“There’s sort of a limited number of possibilities, so the best way of figuring our what those are, and how they might influence the performance of a project downstream, is to be engaged with Stanford,” Lichten said.

, Stanford’s associate vice president of government and community relations, said she had sympathy for the creek authority’s predicament, acknowledging the early stage of the project.

“How they include it in their environmental analysis will be their decision,” McCown said.

But Norman Beamer, president of the Crescent Park Neighborhood Association, said the water board’s letter is another roadblock that’s stopping the authority from preventing flooding.

“The Searsville Dam should not have any effect whatsoever on the immediate Upstream of 101 project, which simply widens the Chaucer Bridge,” Beamer told the Post.

Beamer said the water board is allied with environmental groups that want to get rid of the Searsville Dam and to restore the Palo Alto Municipal Golf Course and the Palo Alto Airport to the original wetlands.

One delay after another

“The Crescent Park Neighborhood Association for years, ever since 1998, has been pushing for what I call a short-range solution, which does not totally cure the flooding problem, but which does cure the 1998 level of flooding or less,” Beamer said. “It’s just not acceptable that this keeps getting delayed for other pie-in-the-sky, long-range goals that may never be reached.”

Lichten said his agency did think there would be a benefit to water quality and flood protection in restoring those wetlands, but that they ultimately issued a permit for the lower portion of the creek authority’s flood protection project above Highway 101 that didn’t achieve those goals.

He added that his agency didn’t have a position on what Stanford should do with the dam, but only that it should be taken into account in the creek authority’s planning.

“Flood management projects in the built urban environment are complicated,” Lichten said. “But from our perspective, the most effective projects are those that are engaged with stakeholders.”

The creek authority’s board will meet at Menlo Park City Hall, located at 701 Laurel St., at 3:30 p.m. today (Jan. 25).