BY DAVE PRICE

Daily Post Editor

It’s a sad situation that has been repeated in Palo Alto many times. A Caltrain strikes a person on the tracks. Ambulances and police rush to the scene. Traffic stops. And then people begin to ask questions. Was it a high school student? People get on social media and offer their own information — what they saw and what rumors they heard. The Post will get phone calls and emails from readers asking if we know what happened.

The vacuum of information causes people to fear the worst. Panic sets in.

Finally, Caltrain posts a statement on its social media account giving the basic information. Over the next few hours, more details emerge. Often the story isn’t as bad as people had feared.

Now Caltrain has decided it won’t give out information about train deaths — leaving people to guess and fill in the blanks on their own.

This policy makes matters worse. When trains stop unexpectedly for an hour or two, when crossings close to traffic, when people see ambulances and police cars at the tracks, they’re going to assume the worst. Responsible media outlets, like this newspaper, will wait for the official word before reporting on a train death.

But Caltrain won’t be able to stop people on social media from spinning their own stories. How long will it be before a person sets up an account on X, formerly Twitter, to broadcast rumors about rail deaths?

Caltrain says this policy is warranted because there are too many copycat suicides. The theory is that when troubled people read or hear that there’s been a railroad suicide, they’ll kill themselves as well.

But we haven’t seen any evidence of copycat suicides. If copycat suicides were taking place, several of them would occur with a day or two of each other.

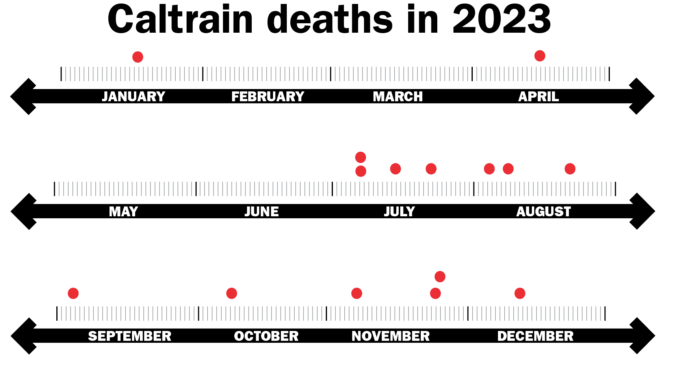

However, in 2023, the 15 deaths that year were an average of 25 days apart from one another.

So is Caltrain saying that a copycat learns about a sucide, then waits 25 days to copy it?

That’s absurd.

Truth is, we’ll never know why people decide to take their own lives because suicide is complex and often caused by a range of factors, rather than a single event or a news report.

But we don’t have the circumstances that would lead experts to say we’re suffering from a case of suicide contagion, the clinical term for a series of copycat suicides.

By keeping this information secret, Caltrain is worsening the stigma surrounding suicide. If it is discussed openly, the embarrassment of seeking mental health counseling is reduced. But if suicide is a big secret, people avoid getting the help they need.

The decision by Caltrain to stonewall the public on death information runs contrary to what the CDC and anti-suicide groups advise.

The CDC, in a report on its website titled “Suicide Contagion and the Reporting of Suicide,” says: “Health care providers should realize that efforts to prevent news coverage may not be effective, and their goal should be to assist news professionals in their efforts toward responsible and accurate reporting.”

The CDC, in its protocols for dealing with suicide clusters, tells local authorities to keep the public up-to-date on their investigations.

“Ongoing effective communication is necessary from reliable spokespersons …,” the CDC’s protocols state. The National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention doesn’t support an information blackout either. Instead, the alliance is asking the media to report suicides responsibly, believing such coverage could do good. Those guidelines include avoiding glorifying those who commit suicide, de-emphasizing the means of suicide and not publishing dramatic photos related to the death. Those guidelines are followed by most of the newspapers and TV stations in the Bay Area, including the Post.

Caltrain’s approach is uninformed and counterproductive. It’s telling that the bureaucrats at Caltrain didn’t bring the policy to the railroad’s board of directors for a public hearing so that the idea of a news blackout could be scrutinized. Actual experts could have warned Caltrain about this approach.

Instead, Caltrain is sticking its head in the sand and hoping the problem will go away. That’s not a solution.

If you are in crisis, please call, text or chat with the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 988, or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741.

Dave Price’s column appears on Mondays.

Common sense is that the media report the deaths but leave it at that — basic reports without any embellishment. This “news blackout” won’t work because of social media. The minute a person dies on the tracks, it will be all over X.

One thing to remember is — don’t listen to the experts. Remember during the suicide cluster, the “experts” were proposing so many illogical things that didn’t work, like starting classes later in the morning, banning Advanced Placement classes, changing the school holiday schedule, teaching kids that they’re victims. The suicides soared. The experts don’t care. They get a regular paycheck and can move on to another town when things get too hot.

Caltrain has a fatality Wednesday afternoon in Sunnyvale. Train service was disrupted.

They don’t want to be held accountable, so that’s why this is going to be secret. Don’t even bother rolling out the policy with a public hearing. Just impose it from the top. “We know better than you do.” Isn’t one-party rule great?

It’s hard to believe that Caltrain is relying on debunked research, the Werther Effect, as its reason for banning public information.

The Werther effect has been promoted by American sociologist David Phillips, who counted the number of front-page suicide news stories in the New York Times, between 1947 to 1968, and mapped them against national suicide rates in the month following the announcement of the suicide.

What does one have to do with the other? Not much.

Phillips claimed there’s a correlation, but two re-analyses only partially supported his claim.

But believing there is a relationship between variables even when no such relationship exists is an “illusory correlation,” wrote psychologist Christopher Ferguson in his study on the Werther effect.

William Proctor of Bournemouth University wrote: “Phillips’ methodology has been widely criticized and the research effectively debunked from within the field itself.”

After analyzing the methodology and findings, James Hittner, associate professor of psychology at the College of Charleston, found that “the Phillips data were not supportive of the Werther effect.”

Hittner goes on: “Perhaps the most central statistical concern is that these studies did not control for the positive correlation (i.e., dependency) between the expected and observed suicide rates before examining the impact of media publicity on the observed number of suicides.”

Hittner said that Phillips’ studies were re-analyzed twice and the only partially supported the Werther effect.

September 30, 2019 article by the University of Bristol self-harm prevention research group says:

“[I]t would be incorrect to conclude that all media coverage of suicide is harmful. Despite compelling evidence, research in the field is characterised by inconsistent findings, with a proportion of research showing no effect,” wrote author Helen Fay.