BY ELAINE GOODMAN

Daily Post Correspondent

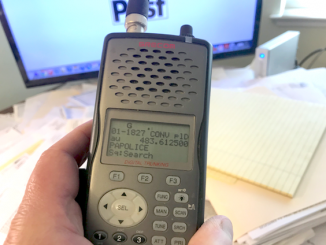

When police in Palo Alto and other cities decided this year to encrypt their radio transmissions, they said they were complying with a directive to keep certain personal information from going out over the airwaves.

But one of the state’s biggest law enforcement agencies, the CHP, is using an alternative that keeps its transmissions available to the public. And the state Attorney General says that police departments may be able to comply with the directive without using encryption.

In October 2020, Joe Dominic, chief of the California Justice Information Services Division at the Department of Justice, sent a bulletin to law enforcement agencies to remind them that they need to protect personal information when using the California Law Enforcement Telecommunications System. Officers use the system, also known as CLETS, to check individuals’ driving records and criminal histories.

The issue is that when officers call dispatch to check on a subject using CLETS, that person’s “personally identifiable information” — such as their name in combination with a Social Security or driver’s license number — may go out over the radio. Dominic’s bulletin said encryption of radio transmissions was one way to solve the problem. While encryption may protect personal information, it also blocks the ability of the public and the news media to use police scanners to hear what officers are doing.

But the DOJ bulletin noted that encryption isn’t the only option. As an alternative, agencies may “establish policy to restrict dissemination of specific information,” the bulletin said.

Police departments including those in Palo Alto, Mountain View and Los Altos encrypted their radio transmissions early this year.

But some police departments are using alternatives to full encryption. One example is the California Highway Patrol, which uses an older radio system that doesn’t support encryption. The CHP instead adopted a policy in October 2020 that limits the amount of personal information that can go out in a single, continuous radio transmission.

The CHP’s method

For example, an officer might ask the dispatcher for a “10-29 check,” which is shorthand for seeing if a person is wanted for any crimes. The officer provides a driver’s license number, such as A1234567. The dispatcher repeats back the license number — A1234567 — to make sure they heard it correctly.

When the dispatcher returns, the driver’s license number is not repeated. Instead, the dispatcher states the subject’s name and information such as whether the person has outstanding warrants. That way, the person’s name and driver’s license number are not broadcast in the same transmission. Dispatch can send additional details to an officer’s computer.

Another part of the CHP policy cautions against saying someone’s full address over the radio.

“Whenever possible, address information should be limited to the city and first three characters of the address,” the policy states.

And officers should use a computer to perform record checks when possible, the policy said.

What does the Attorney General think?

The Post contacted the Attorney General’s office to see what officials there thought about CHP’s approach. The Attorney General’s press office pointed to the October 2020 bulletin.

“The bulletin … makes it clear that law enforcement agencies may use different approaches to protect CLETS-derived information in line with long-standing requirements,” the AG’s press office said.

When asked whether CHP had satisfied the directives in the October 2020 bulletin, the AG’s press office said: “We’re aware of their approach. However, we’re unable to provide legal advice or analysis.”

The Palo Alto Police Department encrypted its radio channels on Jan. 5, with little advance notice to the public or the media.

In March, Police Chief Robert Jonsen sent a letter to Dominic at the DOJ, asking whether radio transmissions could be unencrypted and again be open to the public, while other options are evaluated. Dominic responded to Jonsen in July, saying that after “careful review,” the city is “required to comply with state and federal rules on the encryption” of personally identifiable information, also known as PII.

“The city of Palo Alto cannot revert back to their previous system and broadcast PII on a non-encrypted channel that can be accessed by unauthorized individuals,” Dominic wrote.

During a City Council study session in April to discuss police issues, some council members asked Jonsen to look for options that would protect privacy but still allow the public and the press to listen to police activity on the radio.

Jonsen said on Friday that he doesn’t think a non-encrypted approach is a good option for Palo Alto.

“Palo Alto’s decision to unencrypt would significantly impact the entire system,” he said. “Palo Alto would be on an island and lose many advantages of regional interoperability we have been committed to and investing in for over a decade.”

“In my professional opinion, our dispatch and field personnel would have new barriers that would negatively impact public safety,” he added.

A PulsePoint-like alternative

Meanwhile, City Manager Ed Shikada said the city continues to work on an app similar to PulsePoint, which alerts people to fire and medical dispatch calls with a visual readout. More details might be available in coming weeks, he said.

Shikada said a further discussion with the City Council about police radio encryption isn’t currently scheduled.

Menlo Park police and Menlo Park fire still operate in the clear. I guess Palo Alto Police have more secrets than they do across the creek.