BY ELAINE GOODMAN

Daily Post Correspondent

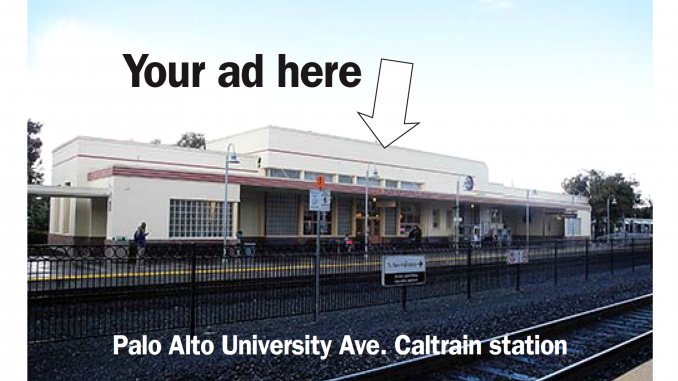

The possibility that Caltrain riders could be pulling into the Brand X — or other corporate name — station is a step closer to reality now that the transit agency’s board of directors has approved a naming rights policy.

The Caltrain board of directors last month approved a policy for selling naming rights to its assets, including train stations, as a way to raise money. Caltrain could solicit proposals for naming rights or respond to unsolicited requests.

So far, the transit agency hasn’t received any requests to buy naming rights to its train stations, Caltrain Chief Communications Officer Seamus Murphy told the board last month.

While the policy spells out some guidelines for naming rights agreements, the proposals would still need approval from the board of directors.

“Unfortunately, I do see the need for it from a revenue point of view,” Caltrain board member Cheryl Brinkman said in supporting the policy.

The policy emphasizes that stations should be renamed in a way that doesn’t confuse riders. Caltrain might require the sponsor’s name to be combined with the existing station name, for example, Station X/Company X.

No Marlboro train

Under the policy, Caltrain could reject proposals considered offensive or discriminatory, or that promote a religion or political view. Similar restrictions to those in Caltrain’s advertising policy would apply, including a prohibition on tobacco company advertising.

Caltrain also could require a minimum number of years for the agreement. Hiring a consultant to assess the value of naming rights is a possibility, Murphy said.

Board member Monique Zmuda said she felt uncomfortable about selling naming rights.

“I hope that we proceed with caution to protect the names of our stations so that our users know the destinations of those and not a company that will come and go, having lived through 3Com Park and AT&T park and others,” she said. “It’s the Giants stadium to me. And the money in some instances may not be worth it.”

Director Ron Collins asked whether purchasing naming rights would give the buyer any control over train systems.

“I’m visualizing a Google train, for example,” said Collins, who is a San Carlos city councilman.

But Murphy said the buyer of naming rights wouldn’t have any operating control over the trains.

On the other hand, Zmuda said, Caltrain might want to consider asking for maintenance help or other services as part of a naming rights agreement.

Salesforce Transit Center

Caltrain is following in the footsteps of other transit agencies that have sold naming rights. Murphy said other naming rights deals have ranged in length from five to 30 years, at prices from just under $1 million a year to nearly $4.5 million annually.

In one of the larger deals, software company Salesforce in 2017 agreed to a 25-year, $110 million sponsorship, including naming rights, of a new transit center in downtown San Francisco.

The sale of naming rights is also raising money for transit agencies in other regions.

In October 2017, the San Diego Metropolitan Transit System announced an agreement with Sycuan Casino to call the trolley system’s 24-mile green line the Sycuan Green Line.

The 30-year agreement was expected to bring in up to $25.5 million for the transit system. The deal followed a 30-year, $40 million agreement between MTS and UC San Diego for naming one of the lines the UC San Diego Blue Line. The deal also included naming rights for a few stations.

The Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority says it was the first transit system in the nation to sell naming rights to its assets. The Cleveland Clinic and University Hospitals agreed to a 25-year sponsorship of the system’s HealthLine; naming rights to stations along the line have also been sold.

RTA officials said that in addition to raising money, the partnerships enhance the image of the transit systems.

The Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority had been poised to sell naming rights to subway stations, bus stops and other assets until the agency’s board of directors repealed the policy in early 2017. A staff attorney told the board that the agency could face lawsuits if it rejected a sponsorship proposal because of a company’s business practices or political affiliation, the Los Angeles Times reported.