BY ALLISON LEVITSKY

Daily Post Staff Writer

Tom Wolfe, the journalist and novelist known for his inventive chronicling of Bay Area counterculture in the 1960s, died in New York on Monday (May 14) after being hospitalized with an infection. He was 88.

Wolfe had lived in New York City since joining the New York Herald Tribune as a reporter in the 1960s — but some of his work in the intervening years formed important cornerstones of California history and lore.

In one of the most popular works of New Journalism — a free-wheeling literary style that let the author write himself into the story — Wolfe revealed the adventures of Bay Area author Ken Kesey and his band of Merry Pranksters in the 1968 non-fiction book, “The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.”

The book took place at Kesey’s two-bedroom cabin in La Honda, where Kesey lived as a Stanford creative writing student in the late 1950s and remained there until the early 1970s with his wife and children.

Kesey was arrested for growing marijuana in the late 1960s and early 1970s. “The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test” was based on Kesey’s experiences working at the veterans hospital in Menlo Park while attending Wallace Stegner’s writing seminar at Stanford. Kesey also volunteered for experiments with LSD.

Peter Richardson, a historian who teaches classes on California culture at San Francisco State University, said he was struck by Wolfe’s East Coast outsider perspective on his sojourns in the Bay Area.

“I think his interest was kind of anthropological. For him, it was so different from his own experience,” Richardson told the Post. “It’s the view of the periphery from the center of the culture.”

Wolfe grew up in Richmond, Va. and graduated from Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Va. in 1951. He earned his Ph.D. in American studies at Yale, then reported at the Springfield Union in Massachusetts and the Washington Post before moving to New York.

“For him it was a big eye-opener. He had a very high opinion of Kesey. He thought he was one of the most important American writers,” Richardson said.

California counterculture shocked Wolfe

Wolfe was also very concerned with status, Richardson noted. The lack of this preoccupation in California counterculture in the 1960s “shocked” Wolfe.

Steve Silberman, a Wired Magazine journalist and Grateful Dead fan who befriended Beat poet Allen Ginsberg in the 1980s, remembered Wolfe as a talent who walked into the right place at the right time.

“Tom was a very sharp observer of a moment in history that turned out to be incredibly pregnant in that it gave birth to everything from the modern jam band concert experience, to immersive multimedia environments, to a new kind of journalism,” Silberman told the Post. “He was incredibly lucky to be incredibly prepared to walk into this scene.”

In 1983, Wolfe returned to the Peninsula and wrote the prescient “The Tinkerings of Robert Noyce: How the Sun Rose on the Silicon Valley” for Esquire.

And almost 20 years ago, he spent time observing university life at Stanford in 1999 in preparation for his 2004 novel on college sexual relationships, “I Am Charlotte Simmons.”

Wolfe’s time at Stanford

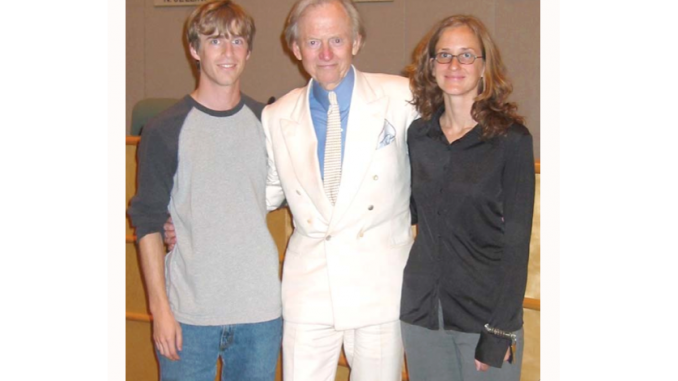

Ted Glasser, a professor emeritus in Stanford’s communication department, remembered Wolfe for his charm and generosity with his time while on campus as well as his seriousness about journalism.

In class one day, Glasser discussed the ethics of the New Journalism technique of fabricating dialogue that the author couldn’t have been there to hear.

Glasser had his students ponder what Wolfe might say about the technique, then surprised the class by asking, “Why don’t you ask him?”

Wolfe stood up from the front row, where he had been quietly observing in his trademark white suit, and answered students’ questions.

“He was just very nice talking to the journalism students,” Glasser said. “Oddly, he wanted to come to campus to background his book and wanted to be inconspicuous, which is impossible the way that he dresses.”

At a dinner with students, alumni and faculty of the communication department at the Stanford Faculty Club in 1999, Wolfe said he thought there was less news covered at the time “than at any time in this century.”

He derided the trend of online journalism, urging young reporters to go after newsroom jobs that let them leave the office.

The advice echoed his remarks in a talk at Stanford the year before.

“Go out into the world and find material,” Wolfe told an audience at the university in 1998. “Ask questions, learn about new environments and then write.”