Cheryl Geidner figured council members in Volant, a tiny borough north of Pittsburgh, Penn. would approve a preliminary year-end budget despite no discussions at public meetings on the proposed financials.

She never figured they’d raise property taxes by 57%.

“There had never been a mention of that,” said Geidner, a property owner who helps oversee a business with her husband, John, in the town of 126 residents. “You didn’t see the budget. You didn’t see the ordinance. I think everybody was somewhat taken aback.”

The plan, given final approval last week, will steeply increase tax bills: A property assessed at $100,000, for example, would have been billed $700 in 2023. In 2024, that bill will rise to $1,100.

The council’s silence leading up to the decision highlights what some observers say is a striking trend toward secrecy among local governments across the U.S. From school districts to townships and county boards, public access to records and meetings in many states is worsening over time, open government advocates and experts say.

But David Cuillier, director of the Joseph L. Brechner Freedom of Information Project at the University of Florida, found that between 2010 and 2021, local governments’ compliance with records requests dropped from 63% to 42%.

High fees, delays and outright refusals from local governments to release information are among the common complaints.

Examples are plentiful.

Earlier this year, officials in a suburban Chicago community — ticketed a local journalist — for what they said were repeated attempts to contact city officials seeking comment on treacherous fall flooding. Officials reversed and — dropped the citations — days later.

In November, open government advocates in California sued the city of Fresno for allegedly conducting secret budget negotiations for years.

In October, residents of Sapelo Island in Georgia, who largely rely on a ferry to get to the mainland, accused county officials of making it difficult for residents to attend important public meetings by scheduling them after the last ferry was slated to depart.

In San Mateo County, a Superior Court judge ruled in 2022 that the East Palo Alto Sanitary District had violated the state’s open meeting law on Sept. 8, 2016, when the district’s board voted to approve a reorganization plan. Among the violations found by Judge Marie Weiner is that the public did not have access to the meeting, as the doors to the building were locked and the receptionist who buzzed people into the regularly locked building had already gone home for the day.

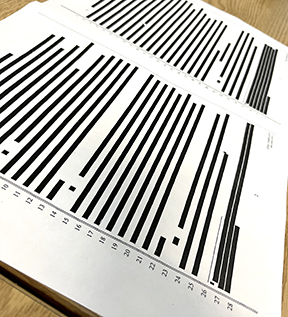

In April 2017, the San Mateo County Community College District filed a lawsuit regarding the botched sale of its TV station, KCSM. The problem? All but two pages of the 33-page lawsuit were blacked out, preventing the public from discovering what transpired with the TV station funded by taxpayers (see graphic above).

Volant, Penn., measures slightly larger than 0.1 square miles, and the latest Census shows it has 46 households in total. The borough’s small-town charm and small-business merchants have made its Main Street a day-trip destination.

The unexpected tax hike could be a burden for the community, where half the population is over age 65 and the median salary is $64,375 – below the statewide median of $71,798.

It’s their first tax increase in seven years.

After the council approved the preliminary budget in November, a local reporter requested a copy of it and was denied. Told to schedule a meeting with the borough’s secretary, the reporter was met by a closed office.

Taped to the door was a five-paragraph explainer from Council President Howard Moss. It included brief anecdotes about rising expenses but no fiscal data to explain the tax increase.

Neither Moss nor the council’s vice president, Glenn Smith, replied to messages seeking comment. At a meeting Tuesday, when the council gave the increase final approval, Smith said the borough has been operating at a deficit for years but avoided raising taxes previously because of Covid and high unemployment.

The state of public access in Volant?

“There is none,” said Bridget Fry, a resident who launched an unsuccessful write-in campaign this fall to join the council. “It’s definitely disturbing, and it’s extremely uncomfortable living there.”

Paula Knudsen Burke, attorney for the Pennsylvania chapter of the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, said too many government officials in Pennsylvania operate under the presumption that the onus is on the requester to prove a record is public. That’s not the case. Records are presumed to be accessible, and the government is tasked to prove otherwise, according to the state’s Right to Know Law.

“While it can make more work for local officials, the Legislature has said these records are available and accessible,” Burke said.

Incidents of governments suing journalists and residents for making records requests also have become more common, said Jonathan Peters, a media law professor at the University of Georgia.

What is becoming increasingly common are so-called “Reverse CPRAs” — a lawsuit intended to keep secret information the plaintiff feels should not be released publicly. The Post was involved in such a lawsuit for over two years after the Silicon Valley Clean Water sewage agency alerted its former General Manager Dan Child that a reporter had requested information related to his mysterious exit — and payout — from the agency.

What the Post ended up finding out through the lengthy court battle is that the agency paid out a total of $1.8 million to two former employees — $875,000 to Child and $1 million to an unnamed female employee who alleged Child had sexually harassed by offering sex advice.

Accessing local government meetings is getting more difficult, too. Elected officials are discussing significant public business in closed sessions, observers say. In some regions, they’re engaging in more combative behavior with constituents.

Researchers have several theories about the new landscape. Local agencies generally lack sufficient staff and infrastructure to efficiently process records requests. Then there is the decline of local media institutions, which have limited resources to wage costly legal battles over access to meetings and records.

Compounding the issue is the increased polarization gripping communities nationwide. Election offices across the country have been flooded with records requests from activists motivated by election falsehoods, piling on work. And school boards, for instance, have become political battlegrounds over Covid policies and curriculum, prompting flurries of records requests, accusations of public meeting violations and intense scrutiny. In some areas, school boards have become dominated by highly divisive members.

“Governments feel emboldened to basically flout democracy (and) say, ‘We’re in charge. Don’t question us. We’re not telling you what’s up,’” Cuillier said.

Palo Alto decided to keep a pandemic-era lockup at City Hall. City Manager Ed Shikada closed the top floors of City Hall to the public at the beginning of the pandemic, allowing only employees with a keycard to use the elevator.

Shikada has kept the upper floors closed in the name of employee safety. All of the chairs and tables have been removed from the lobby, and a computer kiosk replaced a receptionist.

The changes were never announced to the public or discussed by Palo Alto City Council.

Shikada’s spokeswoman, Meghan Horrigan-Taylor, answers questions from reporters rather than having individual employees talk about their projects.

Shikada used to send council members emails with some updates marked as “information for council members only — will not be distributed publicly at this time.” He appears to have stopped marking certain items as private but continues to send council members updates that aren’t released to members of the public unless they file a California Public Records Act request.

A 2023 state auditor’s report revealed multiple problems with transparency in the small town of Rural Hall, North Carolina.

The town failed to produce 38% of records requested by members of the public between November 2021 and June 2022, the report found. The requests included employment history for two town employees, copies of resignation letters and the former town manager’s employment contract.

Long-time resident Carol Newsome was among those who submitted requests. She said the town government “blew up” with turnover in 2021, and she was trying to figure out why.

In denying one resident’s requests, a town official cited the resident’s “demonstrated malice towards Rural Hall,” which was in direct conflict with state public records law, the report asserts.

The report also determined the town council violated state open meetings law by discussing certain matters in closed session.

Ron Niland, interim Rural Hall town manager since January, noted in emails that the individual who oversaw records requests at the time no longer works for the town. He added that during his tenure, the town council has “conducted themselves in accordance with applicable state statutes.”

Newsome, meanwhile, recalled the ease of accessing Rural Hall records just a few years ago.

“You could just walk in or call to the Town Hall and say, ‘I’m wanting to know such and such.’ And they’d say, ‘Well, do you need it printed, or do you just want the information?’” she said.

Now, she views her hometown as “kind of a microcosm” of troubling trends in government overall.

“We see it up and down, and just poor behavior in general,” Newsome said. “The arguments and the pushback from staff and the council became just more hostile and disrespectful than I’ve ever seen. I just hadn’t experienced it in town before.”

Similarly, on the Mid-Peninsula, multiple government entities will require reporters or residents to request documents through a Public Records Act request, when just a few years ago, the document could be requested verbally or through a one-line email. Forcing requests to be funneled through public records requests delays the release of information, allowing the government agency 10 days before the requester can find out when they will get their documents.