Most of California’s 6.1 million public school students could be back in the classroom by April under new legislation announced today (March 1) by Gov. Gavin Newsom and legislative leaders. Critics panned the plan as inadequate.

Most students in the nation’s most populous state have been learning from home for the past year during the pandemic. But with new coronavirus cases falling rapidly throughout the state, Newsom and lawmakers have been under increasing pressure to come up with a statewide plan aimed at returning students to schools in-person.

If approved by the Legislature, the plan announced today would not order districts to return students to the classroom and no parents would be compelled to send their kids back to school in-person. Instead, the state would set aside $2 billion to pay districts that get select groups of students into classrooms by the end of the month.

Crucially, the legislation does not require districts to have an agreement with teachers’ unions on a plan for in-person instruction. That’s a barrier that many districts, including the nation’s second-largest district in Los Angeles, have not been able to overcome.

It also does not require all teachers be vaccinated, as teacher unions had urged and that could take months given the nation’s limited supply of vaccine. The legislation would make it state law that 10% of the state’s vaccine supply be set aside specifically for teachers and school staff.

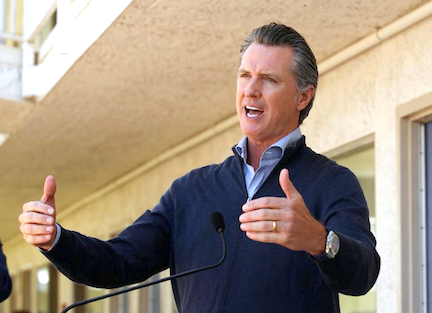

“You can’t reopen your economy unless you get your schools reopened for in-person instruction,” said Newsom, who announced the deal with state Senate President Pro Tempore Toni Atkins and Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon at an elementary school in the Elk Grove Unified School District just south of Sacramento. The district, one of the first in the country to halt in-person learning last year because of the coronavirus, plans to return to in-person instruction later this month.

The state’s two largest teachers unions mostly praised the agreement, with California Federation of Teachers President Jeff Freitas calling the prioritization of vaccines for teachers “a huge victory.” Kevin Gordon, a lobbyist representing many of the state’s school districts, called the plan “a grand slam home run,” saying it “dismantled every impediment to reopening that we’ve had so far.”

The announcement comes at a critical time for Newsom, who could face a recall election later this year fueled by anger over his response to the pandemic. Kevin Faulconer, the former Republican mayor of San Diego who already has announced his candidacy, said the plan Newsom announced “isn’t even close to good enough for our kids and teachers.”

“For months, Newsom has ignored science and left public schools across our state shuttered while private schools are open,” Faulconer said. “For him to tout this as an accomplishment after months of inexcusable failures shows how out of touch he is, and why he should be recalled.”

Money to help struggling students

In addition to the $2 billion, the legislation would give all school districts access to $4.6 billion to help students who have struggled with learning from home. Districts could use this money to add another month to the school year or they could spend it on counseling and tutoring for students who need the most help.

To get their slice of the $2 billion, districts in counties under the state’s most restrictive set of coronavirus rules — known as the purple tier — must offer in-person learning for transitional kindergarten through second grade, plus certain vulnerable students in all grades. This includes students who are disabled, homeless, in foster care, learning English, don’t have access to technology or are at risk of abuse and neglect.

Counties in the next group, known as the red tier, must offer in-person instruction for all elementary school grades, plus at least one grade each in middle and high schools. With new coronavirus cases falling, Newsom said he expects most counties to be in the red tier by the end of the month.

Districts that meet the March 31 deadline get full compensation based on a complicated formula, while those that meet the standards after April 1 get less money. Districts that fail to have children back in classrooms before May 15 won’t get any money.

How many days a week?

The bill does not say how long students must be in the classroom each week. That concerns Jonathan Zachreson, founder of the parent group Reopen California Schools, who says districts could offer classroom instruction for a few hours one day per week and still get the money. He predicted many parents will get excited reading headlines from Monday’s announcement, only to end up frustrated.

“It does not compel any school district to open other than just bribing them with extra money,” he said. “We need to have higher standards for what in-person learning means.”

Newsom dismissed those concerns, saying he is “confident people won’t be gaming the system that way.”

Megan Bacigalupi, a parent advocate with Open Schools California, said she worried there was no urgency to get middle and high school students back to classrooms, noting the agreement does not require all of those students to return for in-person learning.

“Framing this as a reopening deal is blind to the fact that there will be kids that will not be back in school this year,” she said.

California Teachers Association President E. Toby Boyd praised the legislation for recognizing the union’s safety concerns, which were broadcast to state residents in television ads that started running last month. But he criticized the plan for only requiring coronavirus testing in schools located in counties where the coronavirus is the most widespread.

Questions and Answers about the plan

Q: HOW MUCH MONEY IS INVOLVED?

A: School districts in California are locally controlled, meaning the state can’t force them to resume in-person instruction. But it can incentivize them. The plan provides $6.6 billion collectively for districts.

Those that resume in-person instruction by March 31 can tap into $2 billion in extra funding. The longer a district waits to offer students the chance to return to the classroom, the less money it gets.

The other $4.6 billion goes to expanded educational services and other programs to support kids’ well-being and mitigate learning loss. The money could be used to extend the school year or fund summer school programs. Districts could also tap this money to keep supporting distance learning, as most schools won’t have the space to bring all students back to class full-time.

Q: WHO GOES BACK?

A: Any district that wants the money must allow for the return of certain students, regardless of grade, including those who are homeless, those with disabilities, those who lack access to technology at home or other vulnerable groups.

California divides its counties into four color-coded tiers based on the spread of the virus and other factors. Purple is the most restrictive, yellow the least.

Districts must offer in-person instruction for students in transitional kindergarten through grade 2 in districts in the purple tier once county case rates drop below 25 new cases per 100,000 people per day. Once a county reaches the red tier, districts must offer in-person instruction for students in transitional kindergarten through grade 6, as well as at least one grade of middle and high school. Parents can choose to continue distance learning.

There is no minimum requirement for acceptable in-person instruction. Newsom said Monday he thinks once districts start to allow some students back, they will be more comfortable bringing more students in. But local districts and unions will ultimately decide on a timeline and plan that works best.

Q: WHAT ABOUT VACCINES AND TESTING?

A: Vaccinations for teachers are not required to return to in-person learning. But the plan writes into state law Newsom’s commitment to setting aside 10% of the state’s vaccine allocation, with a minimum of 75,000 doses per week for teachers.

Districts that return in the purple tier must provider regular testing of asymptomatic students and staff as well as testing for outbreaks and symptomatic people. But any district that comes up with a return to school plan by March 31 does not have to follow the asymptomatic testing requirement.

Two of California’s major teachers unions, the California Teachers Association and the California Federation of Teachers, praised the allocation of 10% of vaccines for educators. — By the Associated Press